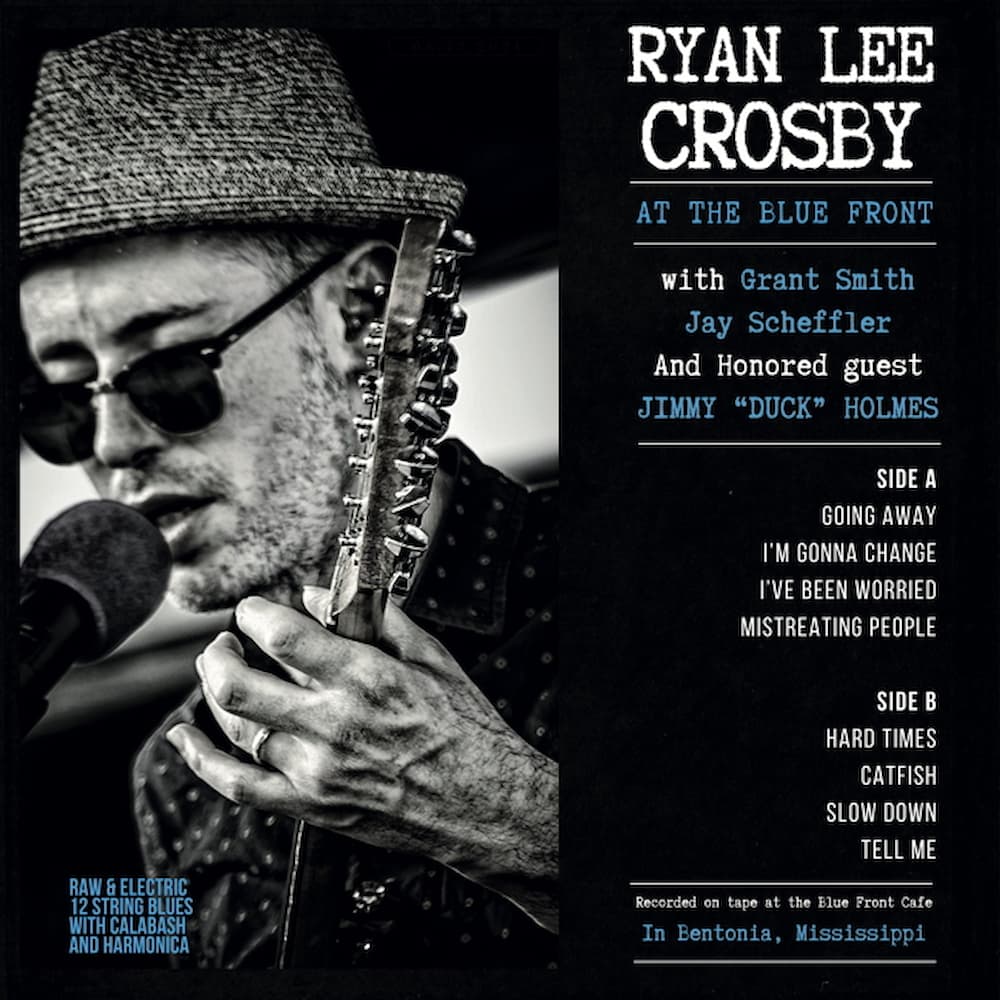

Ryan Lee Crosby

Latest Release

At the Blue Front

Out August 20 via Crossnote Records

Click to download high res photos

Photo credit: Lisette Rooney

Videos

Ryan Lee Crosby, “I’ve Been Worried”

Press

About

Bio:

Ryan Lee Crosby to Release At the Blue Front, Featuring Blues Legend Jimmy “Duck” Holmes, on 8.20.25

Recorded over two days at Holmes’ iconic Mississippi juke joint, the eight-track project offers a haunting, hypnotic meld of Bentonia and Hill Country blues.

Every time Ryan Lee Crosby returns to New England after visiting Bentonia, Mississippi, the feeling he experiences is a kind of revelation — one that emerges anew with each pilgrimage, recentering his perspective, offering a sense of purpose and urging him onward.

“I come back with clarity about what I hope the rest of my life is going to be,” says Crosby, a guitarist, singer, producer and music educator who lives and works in Rhode Island, and was based in Boston for a quarter-century.

To be more specific, Crosby’s destination in that tiny Yazoo County town is the Blue Front Cafe, the hallowed storefront venue established in 1948 and recognized today as Mississippi’s oldest juke joint. With the exception of one fairly recent addition — some welcome indoor plumbing — the Blue Front continues to appear and operate as it has for generations, under the proprietorship of bluesman Jimmy “Duck” Holmes.

Now 77, Holmes is the son of the Blue Front’s co-founding couple, Carey and Mary Holmes. He is also the greatest living practitioner of the Bentonia blues tradition made legendary by Skip James. Holmes essentially grew up inside this heritage at the Blue Front, and learned this soul-stirring music via the blues’ old-school system of apprenticeship, from local masters including James’ contemporary Jack Owens and the originator of the style, Henry Stuckey. Although he’d been an active performer for decades, Holmes only began to record consistently in this century. In 2020 he received a Grammy nomination for Cypress Grove, produced with understated vigor by the Black Keys’ Dan Auerbach, and featuring a band with Auerbach as well as guest guitarist Marcus King.

In its quieter moments, Holmes’ Blue Front Cafe becomes a sort of refuge for Ryan Lee Crosby. Set in the midst of the sparse, rural landscape and unforgiving climate of central Mississippi, it has long served as a haven for its community and visitors alike, providing at one time not only music and hot food but also groceries and haircuts. For Crosby, who has struggled throughout his life with the concept of “home,” the resonance, and the possibility of renewal, he feels inside the Blue Front is singular.

Holmes has been an invaluable mentor to Crosby, in terms of both musical technique and sheer life-affirming fellowship. “He has a presence about him,” Crosby says, “a strong energy and vibrational feeling, even in quiet moments. This reminds me, at times, of Indian gurus I’ve met.”

Throughout Crosby’s remarkable new album, At the Blue Front, all of these elements are palpable, delivering the listener not only to Crosby’s favorite physical space but also to his most cherished headspace.

It was captured on a Tascam 22-4 reel-to-reel at the venue over two focused yet improvisation-rich sessions. The performances feature Crosby singing and playing electric 12-string guitar, with his trusted collaborators Grant Smith on the African calabash and shekere and Jay Scheffler on harmonica. On half of the album’s eight tracks, Holmes guests on guitar and vocals, lending his inimitable spirit to the trio’s already spellbinding chemistry.

His presence also furthers the lifelong process of self-discovery that Crosby experiences through the blues. “I feel like my study of the blues has helped me become a functioning person in the world,” says Crosby. “It’s helped me grow into myself, and it’s something I take very seriously and approach with reverence.”

By his early teens, Crosby had found inspiration in great blues recordings from the likes of John Lee Hooker, Jimmy Reed and Sonny Boy Williamson II. As he developed into a professional musician and a noted guitar instructor, a wide range of interests evolved, including punk rock and post-punk, African music, Indian classical music, songwriting, film scoring and various vital strains of the blues. Among those was the trance-inducing Hill Country blues of North Mississippi, which Crosby learned in part by traveling and performing with the late R.L. Boyce.

About 15 years ago he began to study the Bentonia tradition in earnest, and in the music’s evocative minor-key laments and cyclical, often improvised structures, he found a musical space that related to and accommodated his various pursuits. Crosby saw especially direct parallels between his work in post-punk and the sound of Bentonia and the Hill Country — unique aesthetics, even within the blues genealogy. He found that all of this music shared a striking formal and emotional directness, an ability to captivate with a single mesmeric rhythmic thrust; there is also a common element of foreboding, a tinge of menace that appealed to Crosby’s earnestness as an artist.

“This music just feels to me like a natural extension of who I am — not only my personality, but how I think my mind works, and on a biological level too,” Crosby explains. “There’s something about the sound of a blues-scale melody. … I’ve just always felt at home in that.”

He made his first journey to the Blue Front in early 2019, having studied the music of Skip James for close to a decade and performed it, along with his own compositions, on stages across Europe and the U.S. “I had written a song called ‘Going to Bentonia,’” Crosby says, “but I never thought it would be something that I would actually be able to do.” When he arrived, Crosby recalls, the room “was striking, just as I had seen in photos. … And once inside, it reminded me of punk-rock clubs I had played in years ago.”

Very quickly he was introduced to Holmes, who showed him around and shared some knowledge on guitar. A meaningful connection ensued, as did Crosby’s continuing schedule of visits. In recent years he’s been a regular performer in the annual Bentonia Blues Festival, as well as in shows to coincide with Clarksdale’s Juke Joint Festival.

All of Crosby’s passionate hard work — undertaken both on his own and alongside Holmes over the years — is brought to bear throughout At the Blue Front. Often, Crosby’s songs here meld several strategies into a seamless whole, by blending original music and lyrics, interpolations of blues heritage and lyrical, long-form improvisation. His technique offers crystalline precision, a soulful economy of motion and a deep feel for the pocket.

Crosby’s accompanists are similarly insightful and unobtrusive; Scheffler’s harp provides impeccable melodic and harmonic accents, and Smith’s percussion is a study in discreet intensity. As a trio, they can induce a steady-rolling, foot-tapping hypnosis that only stops when they do. Whenever Holmes joins in, such as on a stunning “Catfish,” the proceedings gather weight and might that can be startling. Think of an already strong wave that hits the right gust of wind and suddenly becomes awe-inspiring.

Actually, riding a wave is an analogue that Crosby chooses to describe the challenge of playing with Holmes, who, in Bentonia fashion, will alter any element of musical form at will. “Everything is unfolding. You can’t stop paying attention, for a second,” he says.

At the Blue Front is also a compelling-sounding recording, with Crosby’s homespun electric 12-string at the fore, filtered through a pedal that gives it a watery Leslie-speaker sheen. He produced it using old-school analog equipment on principle — and on the fly, simply to keep up with Holmes. As Crosby recalls, “There was no ‘Hey, Jimmy, let me make sure I’ve got the right level here.’ There was none of that. It’s like, ‘Is it on?’”

Despite the way the Blue Front acts as a salve for Crosby, the sessions were what you might call a hard-earned pleasure. As always, Crosby put a tremendous amount of planning and thought into this work, and he understood keenly that the challenging means would justify the brilliant ends. Regional conditions can make logistics daunting; between the sessions, Crosby and his skeleton crew encountered a tornado overnight and huddled in hallways, under tables and in closets.

Not that Ryan Lee Crosby would have it any other way. “Playing with Jimmy,” he says, “it’s the joy, it’s the learning, it’s the connection and transcendence and what feels to me like a fulfillment of life’s purpose.”